In 2002, when the American novelist and poet Steven Nightingale and his wife decided they wanted to live in paradise, they headed much farther south, to the sun-drenched Spanish city of Granada, home to the Alhambra palace. In a medieval barrio called Albayzín, mazed with narrow streets “just wide enough for two walking abreast,” with “walls like spillways for flowers,” they bought an old house with a little tower and a hidden garden where their baby daughter could play. “I have never known a place of such concentrated joy,” Nightingale writes. “It felt like something more than being in a neighborhood. It was like being in a mind, where history is musing a secret way forward.”

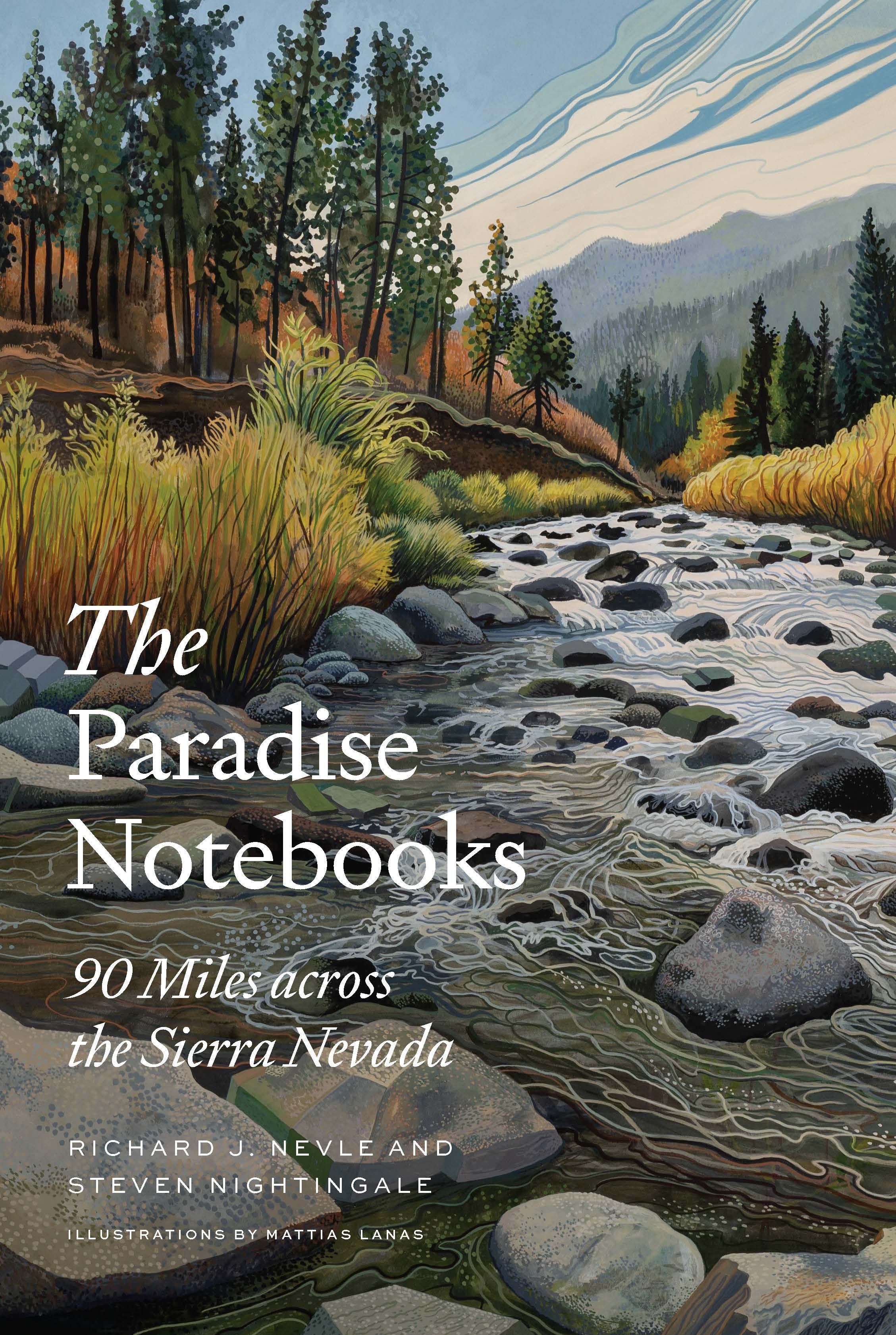

In GRANADA: A Pomegranate in the Hand of God (Counterpoint, $28), Nightingale mellifluously describes the utopia his family inhabited: “The garden and house embraced one another, took up an amorous life together, so that every room came to include air and flowers, trees and starlight, rustling water and ripening fruit. How had this unity, so easy and preternatural, come to be here in Granada?” Investigating his neighborhood’s past, he learned that for nearly eight centuries, beginning in 711, Andalusia was the crown of Spain’s harmonious “convivencia,” when Christians, Muslims and Jews lived and worked together in peace and friendship, producing a rare flowering of art, science and commerce. And then, in 1492, all was lost. Queen Isabella’s inquisitors brutalized the Albayzín, forced Muslims and Jews to convert, confiscated their property and cruelly cast them out.

Over the centuries, the crumbled neighborhood endured, until, 20 years ago, Unesco declared it a World Heritage site, part of the “Patrimony of Humankind.” At the time Nightingale entered the Albayzín, its strong hybrid roots were pushing forth new shoots: The hardiness of the commingled faiths that fed it had endured. His book is not only a memoir of one family’s communion with a dream house, it’s the unearthing of a long-buried dream of civic harmony, a reawakening. Even if you have visited Granada and walked the labyrinthine ways of the Albayzín, Nightingale makes you want to go there again, to see it with new eyes.

—The New York Times Sunday Book Review, reviewed by Liesl Schillinger, May 28, 2015

__________

Above Steven Nightingale’s house in the Spanish city of Granada is a weathervane combining the crescent moon of Islam, the star of David and a Christian cross. It symbolises the convivencia, or coexistence, of three faiths during nearly 800 years of Islamic Spain, a period known today as Al-Andalus. It’s there, he says, “in honour of the past and in hope for the future” – a phrase that could apply equally well to his new book, Granada: the Light of Andalusia.

Nightingale, an American, fell in love in the spring of 2002 with the Albayzín , a medieval barrio, or district, separated by a narrow gorge from the Alhambra, the most famous Moorish palace in the world. He bought a carmen, a house with a hidden garden, arranged to have it renovated, and found, on moving in with his wife and 18-month-old daughter, that the builders hadn’t got started. Meanwhile, he found generosity among lawyers and saw romance even in the light-fingered squatters who had taken up residence before him.

But this isn’t a conventional piece of flit lit by an expat intent on sending up the locals while tending to his smallholding. From sensual celebration of the garden in his carmen, Nightingale moves on to scholarly consideration of the place of the garden in Moorish culture, the history of the barrio beyond it, and then the glories of Al-Andalus, visiting “provinces of mind and experience” from medicine to music.

It’s only over the past couple of generations, he says, that historians have begun to reappraise what was lost with the so-called “reconquest” by the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabel in 1492. Between 711 and that year, Al-Andalus was governed by Christian kings as well as Islamic caliphs and emirs, often with the help of powerful Jewish aides and advisers. There was a “spirit of sustained experimentation” that made for remarkable advances in the arts and sciences. Abulcasis, regarded by many as “the father of surgery”, wrote in the 10th century in Córdoba what became an essential reference text for the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Astronomical tables that revolutionised the study of the subject in Europe were devised by Arabic astronomers, sponsored by a Christian king (Alphonso the Wise), and refined and extended by two Jewish scholars. Centuries before the Romantics in England, poets were celebrating nature in Andalusia.

The convivencia, he acknowledges, was no utopia – “it was subject to breakdown, rivalries, suspicion and stalemate” – but its accomplishments were magnificent. “It is a schoolroom where we might learn, we who even now are failing disastrously to live together at a time with much more dangerous weapons and billions of lives at stake.” He’s right, of course, but he’s also right when he says that “the old, fixed prejudices are still at work”.

A new mosque – the first in Granada since 1492 – opened in the Albayzín in 2003. When I went to see it a couple of years later, I found among the pamphlets in its entrance hall one in English, “Islam Today”, published by a sect named Murabitun, then based in Inverness. It declared that, under the “obligations of a just civilisation”, Muslims were “precluded from taking the jews and christians [sic] as their friends since they are an enemy”.

—The Telegraph, reviewed by Michael Kerr, June 4, 2015

__________

“JEWEL OF ANDALUSIA” - http://www.wsj.com/articles/book-review-granada-by-steven-nightingale-1427483812?mg=id-wsj

—The Wall Street Journal, reviewed by Eric Ormsby, March 27, 2015

__________

One of the delicious literary genres is the book about a writer’s love affair with a city. Mary McCarthy’s Stones of Florence and Edmund White’s Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris come to mind. Steven Nightingale’s Granada takes its place in that radiant company.

—Robert Hass, author of What Light Can Do and The Apple Trees at Olema

__________

Opening Steven Nightingale’s lyrical Granada is to split a pomegranate that pours out a galaxy of seeds. Take the book with you to a garden. There, as you read, the seeds will give forth branches of poetry, music, science, mathematics, philosophy, agriculture, medicine, and all the marvels of Andalusia. Twining, they stretch up toward the brilliant sun—maybe beyond, to the divine. Yet even as they transport you on their various journeys they remain rooted in a family garden in Granada—a beautiful garden that, thanks to the author, you will know and love as he does.

—Thomas Christensen, author of 1616: The World in Motion

__________

This is a highly sensitively written book written by a very fortunate American author who records his visit to Andalusia (Spain) with his family to discover the immense gift to civilization the earlier Spanish community has been.

I can certainly recommend this book to all who have yet to learn how vibrant and productive the integration of Judaism, Christianity and Islam can be. Nightingale chooses the 800 years between 711-1492, in Spain.

This book can so clearly introduce you to such as the Brethren of Purity, Pythagoras, and the traditions underlying the magnificent geometry of the Al-Hambra in Granada. Not to mention the luminary Ibn Arabi, the great Sufi philosopher.

—Keith Critchlow, author of Islamic Patterns and The Hidden Geometry of Flowers

__________

In flowing precise poetic speech, Stephen Nightingale bequeaths us the beautiful and tragic essence of Spanish history, philosophy, and literature, especially poetry, mystical and secular, with Lorca in his Granada. In Granada and Al Andalus we encounter the great Moorish architecture, song, and writings. None since Gerald Brenan in the 50s has so lovingly mastered Spain in its Gothic, Muslim, Jewish, and Spanish faces. Who reads this book relives all Iberia, from medieval convivencia to Franco nightmare. El cante hondo, the deep song persists. A profound delight.

—Willis Barnstone, author of Sunday Morning in Fascist Spain

__________

This beautiful book is a love story: that of, first, a young family falling hopelessly in love with an old house in the medieval quarter of Granada, and their painstaking restoration of the house and its gardens. Then their growing love of the place itself, as they learn the ancient stone streets of the Albayzin while walking their small daughter to school. They become immersed in the dense and complicated history of Granada, even as the mythic Alhambra soars on its promontory above the city.

But this is also a story of what love can do when various peoples put aside differences and work together: for nearly eight centuries, from 711 to 1492, Jews, Christians and Muslims lived in productive, collaborative harmony, translating one another’s holy texts and sharing collective wisdoms, from literature to algorithmic logic to color theory.

Thanks to Steven Nightingale’s glorious and inspiring book we can glimpse what life might become were we not plagued, as we are in these modern times, by religious fundamentalism and hyper mechanized tools of war.

—Jane Vandenburgh, author of The Wrong Dog Dream

__________

Steven Nightingale’s GRANADA: A POMEGRANATE IN THE HAND OF GOD is the rarest delight — a book that is as wise as it is vibrant and alive. To read its pages is to be transported back in time through centuries, interwoven with folklore, history and with the dreams of mankind. I recommend this book most highly. It opens a window into a magical world, an Andalucian garden all of its own, one inspired by Paradise.

—Tahir Shah, author of The Caliph’s House

__________

Granada… is a primordial history of Andalusia, the rose and the magdalena, the throne and the cross—but more than these, it is a sinuous and searching biography of the heart of southern Spain. Nightingale has woven us in its antiquarian spell and I, for one, emerged in Plaza Larga with seven centuries of relative religious calm and extraordinary intellectual and artistic achievement, only to find a king and queen that would bring this great culture to its knees. And yet, like García Lorca, Nightingale summons the duende, the creative force that emanates from this sorrow, so that in the end, this book is really a testament to what can be possible with the spiritual attainment of peace. I cannot remember the last time I have read a story that is literally blood and truth born across two millennia of human understanding. Like a wind from the Sufi masters, it will shake the most austere and humane alike.

—Shaun T. Griffin, author of This is What the Desert Surrenders

__________

Poet and novelist Nightingale (The Wings of What You Say, 2013, etc.) makes his nonfiction debut in this rhapsodic paean to the Spanish city, where he, his wife and young daughter now live part of each year. For the author, Granada is nothing less than idyllic, with verdant, sun-dappled gardens fragrant with orange blossoms; enchanting labyrinthine lanes; and a “rambunctious diversity” of friendly, gentle and wise neighbors who display a “helpless love” for children: “They know that children have been recently formed in heaven and so on earth need special devotions.” A “sainted notary and his equally blessed wife” provided housing for Nightingale and his family while their house was being renovated by nimble craftsmen, one “with the bearing of an Arab prince.” In spring, the “garden and house embraced one another, took up an amorous life together,” and sprouted grapevines and honeysuckle that grew into the bedrooms. In search of Granada’s glorious past, though, Nightingale discovers brutality. While the city thrived during the “lustrous” Al-Andalus period, from 700 to 1492, when Muslims, Christians and Jews coexisted, for the most part amicably, and arts and sciences flourished, conditions changed dramatically in 1492, when Ferdinand and Isabella decided to purge the area of Jews and Muslims. During the Spanish Inquisition, mosques and synagogues were razed, property confiscated, more than 5,000 books burned, and those who refused to convert to Catholicism were massacred. By 1620, the once-populous city was reduced to 6,000 who lived among rubble. In the next three centuries, the deterioration worsened, and the city became a refuge for anarchists; during the Spanish Civil War, fascists took hold. Not until 1994, when it was named a World Heritage Site, did Granada begin to revive. A romantic, at times overly sentimental homage to a city “perfected by catastrophe” and transformed into a place of “concentrated joy.”

—Kirkus

__________

Don’t expect (as I did) a Parrot-in-the-Pepper-Tree type collection of comedic mishaps and tales about the joys — and perils — of joining a new community. This is, more than anything, a history book, albeit one in which the writer’s deep love of his adopted home (Granada and, more specifically, the Albayzín, the district he lives in), his family and his neighbours makes every sentence sparkle. Even better, it’s a history book that assumes no knowledge on the part of the reader. Steven Nightingale covers centuries of events in Spain, describing them with clarity and in a typically engaging style. He starts with the Moorish occupation of Spain in 711 and ends post-Civil War. Despite its vast chronological span, the book is more than a dry recounting of events and dates. Yes, that information is there, as befits any good history book. But Steven Nightingale’s focus is more on the effects of these historical events, and the achievements of the times, particularly the ongoing legacy of the Moorish occupation. He writes in detail about Arabic poetry, the timeless nature of love, developments in maths, science and the arts, geometry in tiling, and much more.

Steven Nightingale also talks, of course, about conflict, religion, convivencia, the dramatic backward slide of the country following the Christian Reconquista, the Inquisition, the maelstrom of the twentieth century… Reading a book about Spanish history could indeed be a maudlin experience. However, he manages to end with a positive message of hope: the modern Albayzín, his beloved home, which he portrays as a beautiful, safe and loving community, is in fact the product of centuries of death and conflict, the perfect example of good arising from something evil. Likewise, his section on Lorca dwells more on the beauty of Lorca’s work, and the immense popularity of the poet and playwright today, than on the tragedy of his death (although his description of Lorca’s final months is typically sensitive and considered).

The timeline jumped around at times: a more chronological narrative would have made this book a slightly easier read, and more useful as a reference book. This is compensated in part by a good index, however. And most pleasing is the excellent, wide-ranging bibliography that makes you itch to get to a library.

This book is a love story, a history book, a homage to victims of intolerance and mistrust, a celebration of the magic of human achievement. Read it then book your flight.

—The Bookbag

__________

The final battle in history’s longest war was fought in 1492, when Spain’s Christian forces conquered the Moorish stronghold of Granada.

What the Muslims left behind was one of the most sumptuous cities in Europe, crowned by the Alhambra, which Steven Nightingale rightly praises as ‘the finest Moorish palace in the world.’ The greatest monuments of Islam are not to be found in the Muslim world. They are in Spain, and the grandest of all rises above this city in which Nightingale has made his home. Granada is exalted with passion, elegance and historical rigour in this delightful account.

It was love at first sight for Nightingale, when in 2002 he wandered into Granada in quest for a place to live. The story unfolds as a personal narrative, as Nightingale marvels at the outpouring of local hospitality, negotiates the tribulations of house repairs and contemplates his daughter’s assimilation into Andalusian life. His personal adaption forms the backdrop to the history of Granada through the centuries.

The voyage sheds light on the many scholars, mathematicians and enlightened rulers who epitomised the city’s unique character. Consider Caliph Abd Rahman III, who in the tenth century was a patron of the arts and sciences, a military genius and a product of the criss-cross of cultures that engendered so rich a legacy: a Muslim who governed with the help of Christians and Jews.

Nightingale takes us through darker periods too: the civil war and the execution of poet Federico García Lorca tell a less joyful story.

However, these episodes notwithstanding, ‘If anyone wants to be rocked by currents of beauty and infamy, Granada is the place.’

—Geographical Magazine, reviewed by Jules Stewart, August 1, 2015

___________

For eight hundred years, beginning in 711 A.D., a magnificent culture of creativity and tolerance known as Al-Andalus flourished in Andalusia, in southern Spain. It was a period never again equaled “for daring, brilliance, or productivity,” writes Steven Nightingale in this exhaustively researched, exquisitely written book. Moslems, Jews, and Christians lived in harmony. Art, science, mathematics, poetry, agriculture, philosophy, invention: each wove its way into the fabric of everyday life.

Then, brutally, darkness vanquished light. In 1492, the armies of Ferdinand and Isabel conquered Granada. So began five centuries that were to Al-Andalus as night is to day. Ethnic cleansing, expulsion, starvation, book burning, the Inquisition. The nightmare would not end till the death of Francisco Franco in 1975, and the subsequent restoration of democracy to Spain.

How does one account for this wild flowering, and for its tragic reversal? Nightingale, a much-admired poet and novelist, is the ideal person to engage this conundrum. In 2002 he and his wife Lucy purchased a home in the heart of Granada’s Albayzín, across a narrow gorge from the Alhambra, and with their year-old daughter Gabriella took up residence there. In the weft of his adopted city, Nightingale discovered a jubilant reincarnation of Al-Andalus: art, music, poetry, dance, literature; most of all, peaceful coexistence among its citizens. “It made one think the world has a goodness at the heart of it,” he writes. Granada is a place of “concentrated joy,” “where walking is like flying.”

So prepared, he undertook a decade-long inquiry into Granada’s past. His meticulous research into Al-Andalus and its violent reversal yields pages that are, by turns, breathtaking and heartbreaking. The tiles of the Alhambra lead him to Al-Andalusian geometry and to the primacy of unity in contemporaneous thought (art and science are mere extensions of one another, for example), which leads him to the teachings of the Sufis. On this side of 1492, by contrast, he finds endless war, corruption, massacres, squandered wealth, and twelve thousand men and women burnt at the stake. Despite sedulous inquiry, he is unable to turn up a single Spanish scientist known to have made a pivotal invention or discovery between 1492 and 1900.

There were lights in the darkness, of course. The one that shines brightest for Nightingale and that yields the book’s finest pages is the poet and Granada native Federico García Lorca. Though murdered by Fascists in 1936, Lorca emerges here as an irresistible force, one destined to be central to the reemergence of Spain from the ashes four decades later. Nightingale illuminates and celebrates Lorca’s three “sources of creation”: flamenco, a music of deep remembrance and release; cante jondo (“deep song”), physical and spiritual unity with earth; and duende, a complex and mysterious quality that is bound up with music and poetry, with physical passion and incendiary soul. “And, most of all,” Nightingale adds, “with Andalusia.”

Four decades after Franco, a miracle: the Albayzín has been “perfected by catastrophe.” For Nightingale, it is one of the best places there will ever be to live. “The streets hold the spirit of cante jondo: let history come with death and ruin, and deep song will rise in time with a beauty that cannot be killed.”

Each page of this deeply personal book is a revelation, and a confirmation that darkness is never permanent. Darkness begets beauty. Nightingale writes that conviction into every sentence.

—Robert Leonard Reid, author of Artic Circle and Mountains of the Great Blue Dream