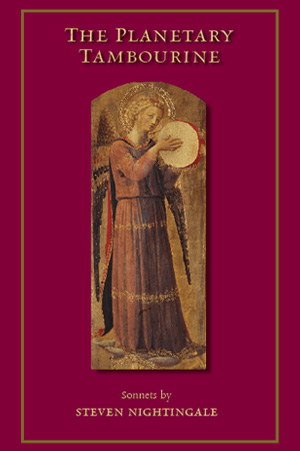

Order: |

Reviews“Steven Nightingale’s collection of sonnets is finely wrought and full of light. Formally elegant, this book is testimony to a life richly lived. The sonnet , as Neruda has famously reminded us, is a little house. The ninety nine poems in ‘The Planetary Tambourine’ are a fine addition to the tradition. Many are poems of marriage and familial love, transformative, healing, good.” Steven Nightingale proves once again that the sonnet, like rock n’ roll, will never die. |

IntroductionIn the thirteenth century, the tumultuous court of Frederick II brought together the cultures of the Mediterranean, and their languages—Latin, Arabic, Italian, Hebrew, to name a few. Among the specialties of the court were poetry, mathematics, war, ornithology, law, and the natural sciences. And among the poets, one Giacomo Lentino wrote verse in an extraordinary new form. It is named, and first discussed, by Dante, who called it the sonetto—our sonnet. Nature invents wondrous physical forms—say, an eye, to convey the signals of light; or a hand, to know the texture of creation. The sonnet, as well, is an invention with a special role: it works in concord with nature, to call the mind close to life. Eight hundred years later, the form endures. In each century, sonnets are written and cherished. With fourteen lines, and a set meter and rhyme scheme, the sonnet is meant to hold beauty and safeguard understanding. The sonnet is a lens. Looking through it, we may see, beyond the thicket of daily events, a world present, lovely, and permanent,. I began writing sonnets thirty years ago, setting down one sonnet a day and four on Saturday. I was waiting tables and dealing blackjack at the time. I wanted a disciplined, restrictive form, so as to learn the essentials, to enter into tradition, to connect with the past. My intention was to move on and write more loosely organized verse. I found the discipline to be exquisite, and the restrictions to hold a joyous liberty. And so to this day I carry on with sonnets. It is as though a young love affair, against all the odds, had turned into a delicious and durable marriage. It’s more than I could have hoped for. These sonnets have been written in a promiscuous variety of places—in a ranchhouse far out in the Great Basin, in boisterous, remote bars throughout the American West, by a campfire in a big canyon in Utah; in New Delhi, San Francisco, Andalusian Granada; in a blue church by the sea in the tropics, in a cabin by a green river in the Sierra Nevada. The manuscripts are folded and tattered, stained with coffee and red wine, and, best of all, marked with my little daughter’s words and drawings in crayon. Sonnets, like all beautiful forms, are alive. Being alive, they dream. Most of all, my reader, they dream of this very day, of being at last in your hands, and of belonging to you. S. N. |

|